Dunford House: the case for preservation

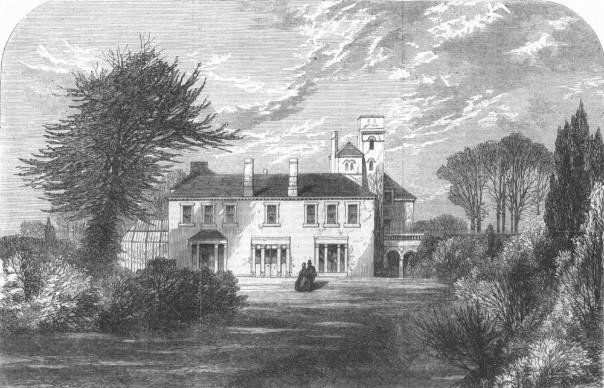

Dunford House, while no architectural masterpiece, has played a significant part in the life of the nation, and the case for preserving its original fabric as designed for the family of Richard Cobden (1804-1865) is strong and compelling.

It is so on three main grounds:

1. Dunford as a unique example of the home of a leading middle class politician of Victorian Britain. Most preserved Victorian houses tend either to be those of the aristocracy or those of wealthy capitalists imitating their lifestyle. Dunford however was rebuilt c. 1848-53 as a family home for Britain’s leading but by no means wealthy middle class politician. It has therefore ever since been associated with the values of free trade, peace, and international goodwill which Cobden’s career exemplified. From Cobden’s letters and other records we can gain a good sense of rebuilding process, with its characteristic Victorian features such as the Paxtonesque glasshouse and the delightful and pleasing library in which some of Cobden’s own books are still displayed, although regrettably others (including his copy of the Great Exhibition catalogue have recently been disposed of). Dunford as much as Parliament was the basis of Cobden’s later political career from which he wrote thousands of letters designed to influence his contemporaries and political life. He also received many political friends and foreign visitors, some of whom recorded the impact of ‘fireside chats’ at Dunford on their future careers. To my knowledge no other comparable nineteenth-century middle class political home survives. Dunford is therefore unique for its insights into the domestic basis of Victorian middle class political culture, and this is reflected in its surviving artefacts including family portraits.

2. Dunford as a cradle of feminism – a suffragist and suffragette home. After their father’s death, the Cobden sisters who had been brought up at Dunford and lived there for some time afterwards were to play an unusual part in later Victorian life. Annie (1853-1926) who married the Arts and Crafts publisher Thomas Cobden-Sanderson, became a leading suffragette, while Jane (1851-1947) who married the Progressive publisher Thomas Fisher Unwin and who retained a strong local presence into the 1940s, was a leading suffragist and one of the first women members of the London County Council, among many other radical causes she supported. She has recently featured in the TV Ripper series, and the sisters are given a chapter in Patricia Cornwell’s Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper, Case Closed (2002) A third sister, Ellen, later a novelist (Dunford appears thinly disguised as Dunton in one of her novels), married the leading artist Walter Sickert, presumed by Cornwell to be Jack the Ripper. At least one of Sickert’s works is I believe is presently at Dunford along with other artefacts, while the library contains volumes bearing the nameplate ‘The Daughters of Richard Cobden’. Dunford therefore played a highly significant part in the genesis and development of later Victorian and Edwardian feminism.

3. Dunford as a centre for global society and the international community. Cobden’s career as the ‘International Man’ has been fully reflected in the later history of Dunford. Although this has not been fully documented, in the Edwardian period it acted as a port of call for many foreign visitors attracted by its associations with free trade and peace, such as the French Society of Economists. After a brief spell as weekend retreat for students and staff of the London School of Economics (1920-24), in the later 1920s it became a real microcosm of aspirations towards a global society, hosting a series of conferences (including the first in Britain devoted to a ‘United States of Europe’ and a series of lectures by distinguished internationalists such as Nicholas Murray and Moritz Bonn. This was done under the aegis of the Cobden Memorial Association and Francis Hirst, a leading Liberal publicist and former editor of The Economist who had married a great-niece of Cobden’s in 1903. Artefacts relating to this period are preserved at Dunford (for example, a visitors’ book) as well as many archives in the WSRO. Nevertheless, the 1930s proved less conducive to the values of Cobden’s internationalism and the property of the Dunford House Trust was offered to the National Trust, 1935-36.

Overall therefore it is clear that, in addition to its part in local life (on which others are better qualified to comment), in the three above respects Dunford House has played a significant part in major aspects of British (and international) history; most houses preserved for the nation can normally make only one such claim.

Anthony Howe, Editor, The Letters of Richard Cobden (1804-1865), four volumes, Oxford University Press, 2007-2015)

Professor of Modern History, University of East Anglia